‘I Applaud These People Three Quarters of a Century Later’

Jerry A. McCoy always had a premonition the Georgetown Branch Library would go up in flames.

So strong was this premonition that he bought a chain ladder from Hechinger, and settled on the two items he would grab: An 1822 portrait of freed slave and Georgetown entrepreneur Yarrow Mamout, and a bound volume of the Maryland Gazette from 1776. One under each arm.

In 2007, when the three-alarm fire began, Jerry was three miles away.

‘I stood on R Street and I just cried,’ says Jerry, Special Collections Librarian for the Peabody Room, previously housed on the library’s second floor. ‘I pictured all of the house files going up in flames, and there’s no way to recreate those.’

The Peabody Room lost 10% of its collection that day, particularly devastating to a man who’s spent the last 17 years working in the name of preservation.

Three years later, the library reopened and the Peabody Room moved to the third floor, as much of its damaged art—including Yarrow’s portrait—was conserved. Miraculously, the Maryland Gazette wasn’t touched.

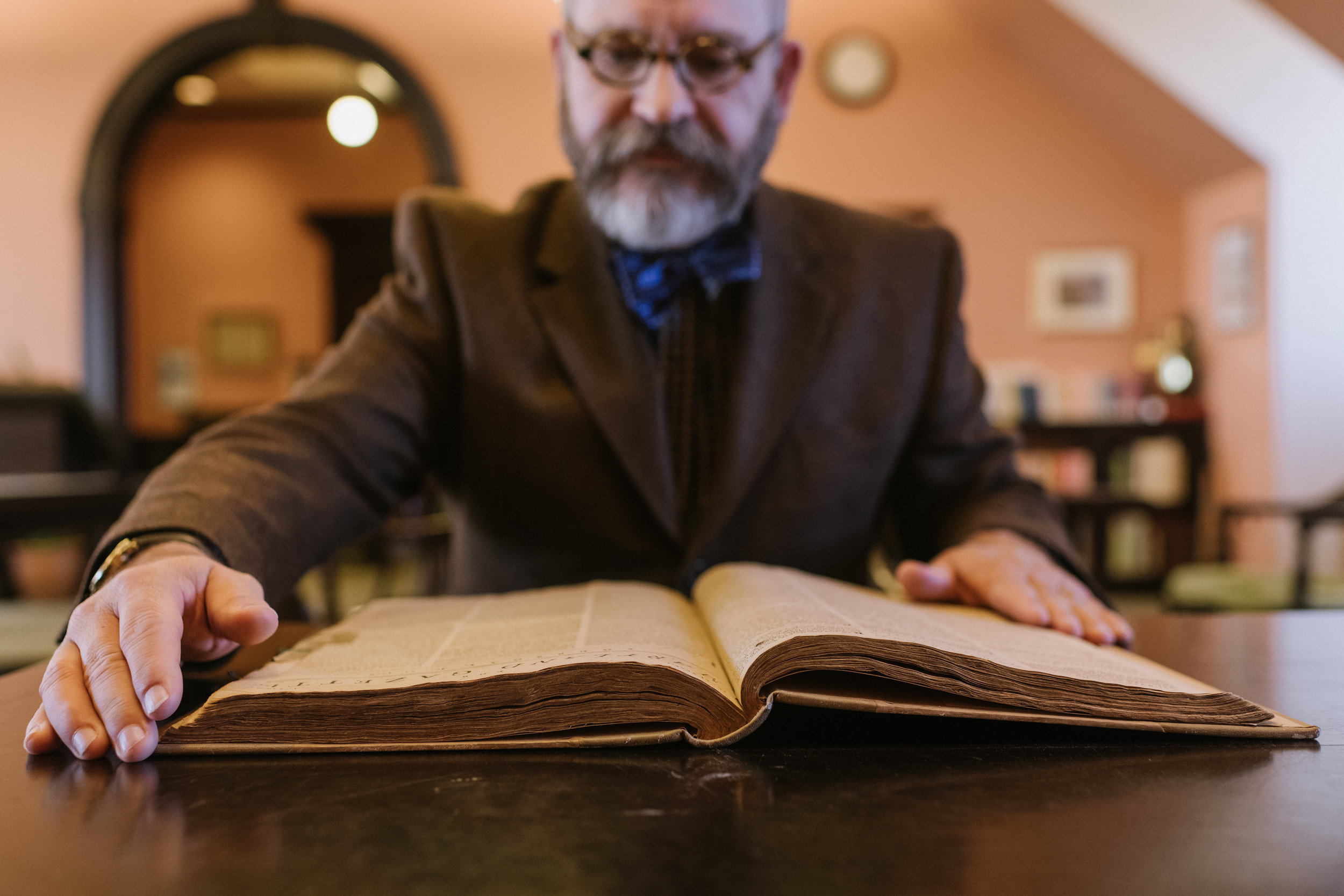

The oldest piece under Jerry’s care, it was the first weekly newspaper published south of the Mason Dixon Line. The entire volume is interesting, but it’s the July 11 issue that still gives Jerry goosebumps.

‘You open the book to that issue, four pages long, and the text of the Declaration of Independence is buried on page 2. Back then there were always these declarations being proclaimed, but I love bringing this one out and saying, ‘but this is the one that stuck.’ It just amazes me to see ‘in the course of human events,’ and it appears like a news story.

Jerry’s career is a study on the course of human events. The former public relations photographer grew up in the ‘economically depressed’ city of Lorain, Ohio, where he learned about his hometown’s local history in eighth grade.

‘It just opened my eyes. I had no concept that history could trickle down to that level. Up until that point it was just world history, or American history, presidents, wars. The bug bit and I’ve just been into local history ever since, wherever I live.’

Jerry moved to the DC in 1978, and has spent the past 24 years living in Silver Spring with his wife, where he serves as the founder and president of the Silver Spring Historical Society. When his PR career came to a halt in the late 90s, he decided to pursue his childhood passion and went to library school.

Today, Jerry splits his time between the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library and the Peabody Room. After nearly two decades, Jerry is still madly in love with his job.

‘I forever remain in awe of the Georgetown neighborhood. This community knew back in the 1920s and 30s that they had something that was special and they wanted to preserve it. I applaud these people three quarters of a century later, because that was before the historic preservation movement of the 60s and 70s. And now, when I drive to work every morning and I get to the top of the hill at R and Wisconsin and see the neighborhood laid out before me, I just feel like here I get to go play for another eight hours preserving this history and helping patrons learn about their community and their homes.’

No day is the same, though Jerry says the biggest draw at the Peabody Room are the house histories. He has a physical file on almost every residential address in Georgetown since 1935, full of article clippings and anything he or his predecessors may have come across related to the house.

‘I get a lot of prospective residents and real estate agents. History sells here in Georgetown. If you can throw in a few historical tidbits in your brochure, it bumps up the house value.’

Students from elementary school to college also pay Jerry a visit when they’re working on a paper, as do authors writing works of fiction set in Georgetown during specific time periods. And then there are the tourists—Jerry’s favorite.

‘I’ve asked the staff downstairs, if a tourist comes in to use the bathroom, send them up here to me! Typically they at least know about the Kennedy connection. If they don’t know about Kennedy, they know about the cupcakes.’

But Jerry isn’t just a repository of well-known history. He’s also well versed in hidden Georgetown—the history that isn’t reflected in most tour books.

‘On O Street east of Wisconsin Avenue, there was a slave pen that was torn down in 1904 and six rowhomes were built on its foundation. Whenever I’m down there, I’ll veer off and walk down the alley. I brush my fingertips down the stone foundation and it just gives me goosebumps thinking of the terrible history those stones witnessed, and the fact that the people who live in those rowhomes are probably oblivious to that fact.’

And then there’s the man to whom the Peabody Room is named after—the relatively unknown father of modern philanthropy. As Jerry will eagerly tell you, George Peabody came to Georgetown from Newburyport, Massachusetts, in 1812, at the age of 17. His uncle opened a dry goods store at the corner of M and Wisconsin, but George soon left and made his millions in Baltimore, importing dry goods from England, and from banking and financing. When he died, he left $15,000 to Georgetown to establish the Peabody Library Association—opening in 1876 across from St. John’s Church.

‘A generation later, Carnegie did the same thing and everyone knows him. Nobody knows about George, so I serve as his PR agent.’

Whether it’s remnants of our country’s ugliest history, a portrait of a local benefactor, or records from an old Georgetown business, Jerry says it will all matter to future generations—generations who have more in common with their ancestors than they realize.

‘People then have the same concerns we do now. Their health, their financial solidity, passing on something to their children. These are common values that go from century to century.’

Under the DC Public Library system, The Peabody Room relies on the generosity of strangers’ donations, as well as Jerry’s own research. (‘There’s no end to the rabbit hole you can go down.’) Although he considers Yarrow Mamout’s portrait the crown jewel of the Peabody Room—on loan to the National Portrait Gallery until summer 2019—his favorite piece at the moment is a painting depicting the Georgetown riot of October 1970 in front of the Georgetown Theater on Wisconsin Avenue. Jerry got an email out of the blue from the painting’s owner, but knew nothing of the riot and wasn’t convinced it actually happened until he started researching.

‘I was just giddy being gifted this. It’s not 1870s or 1770s, it’s 1970s. It brings up-to-date the things I’ve been hoping to acquire for the collection. And pretty soon, 1970 will have been 50 years ago.’

In another 50 years, the Peabody Room collection will be under someone else’s watchful, loving eye. Jerry considers himself a temporary caretaker of its history, only the fourth long-term curator or librarian since the room opened in 1935.

While little is known about the first three Peabody Room stewards, next year Jerry will surpass his predecessor’s tenure. He has a file of each in the Peabody Room, himself included.

‘Fifty years from now, they’ll know who McCoy was.’