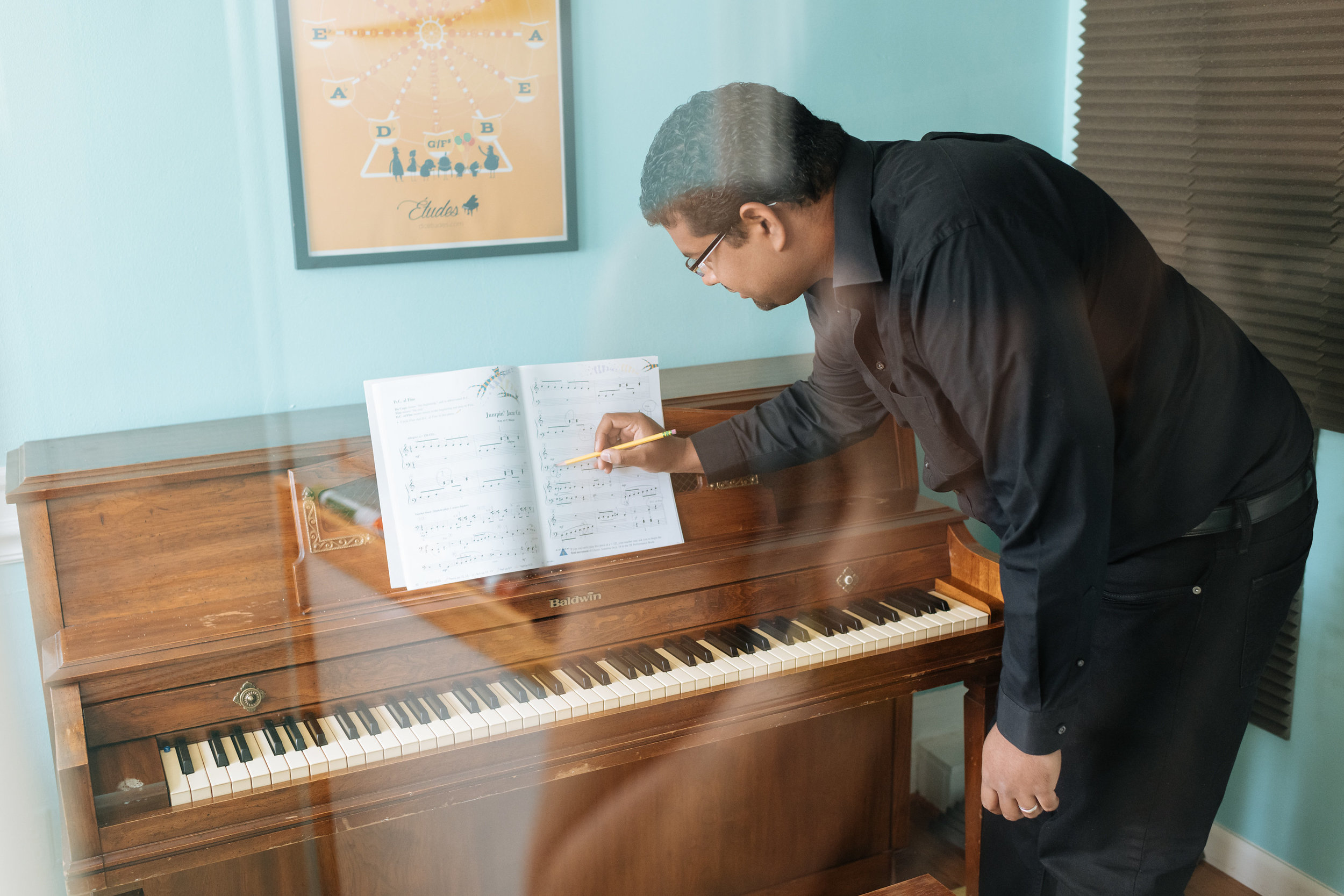

‘I Can Get Lost in the Music’

Eighty-eight keys compose the soundtrack to darren shillingford's life.

‘There are times when playing the piano feels like work. Plink, plink, plink. But if a piece evokes that emotion for me, I can get lost in it. I understand every single note, and the space and the time I’m creating in the song that’s impactful and sending a message, or creating an environment. All of that is magical.’

Born and raised on the tiny Caribbean island of Dominica, Darren began playing out of necessity. His sister saw a movie about a pianist and asked their parents for lessons. They agreed, on one condition. Seven-year-old Darren had to join.

‘I wasn’t having it, but my parents weren’t going to pay for someone to stay home with me. My sister eventually dropped out, and I stayed. One day I was at a restaurant and my aunt said, ‘Go up and play something.’ I played, and with the little applause I got from the crowed, I was like this feels good. That gave me a boost. I was coming home and practicing an hour a day, every day, really at it.’

Darren grew up in an island culture that nudged children toward ‘functional career paths’ in medicine and law. He wasn’t exposed to much classical music until the Internet emerged, trying to close his gaps in knowledge with the best compositions and conductors he could find online.

By the time Darren was a teenager, a shortage of music teachers prompted him to help some of the younger pianists. Teaching offered a different perspective for improving his own techniques, and planted the seed for a future career.

At Florida International University, Darren tried to appease his head, and his heart—following a pre-med tract with a double major in biology and music education. Both his biology advisor and music professor questioned his sanity.

‘The breaking point was, oh God, these chemistry courses! It would be midnight, the library was closing, and I was filling my brain with organic chemistry. Then I would go to the music school and practice. I didn’t think I could survive doing both, and I knew I had to make a decision—especially in pre-med, where they’re like, ‘If you get a B, just change career paths now.’’

When a scholarship opportunity arose, Darren thought he’d have a better chance applying under music education. He received the scholarship, and left medicine behind.

‘Music has been a love / hate relationship, as any passion is. Teaching is so rewarding, and there are days when you’re like all of this is wonderful—accompanying, performing in London, and these opportunities I’ve gotten to play state funerals and events on the islands. But there are some days, pay wise, you’re just like…ugh.’

On those days, it’s the kids who buoy him. Now living in DC, Darren works for the Children’s Chorus of Washington, and teaches two piano classes at Georgetown’s Etudes studio. His teaching style is heavy on preparation—influenced by a fear of solo performances that still follows him after two decades.

‘Put me on the stage by myself—horror show! Even accompanying can be nerve-racking sometimes, because there’s a heightened awareness of watching the director. In a split second if something happens, you have to recalculate. But I find solo performances so intimidating. You need to play all the notes, because everybody knows the music. You can’t skip that note; Mozart will roll over in his grave.’

Drawing upon his own experiences, Darren is intent on making his students as comfortable as possible.

‘There’s going to be jitters, but I rehearse them to a point that it’s almost rote,’ says Darren, also a self-taught organist. ‘The one thing I can control is that they are fully prepared.’

Darren says he’s inspired by each child’s personal journey, often wondering what became of previous students, and if they remember him.

‘I like seeing the kids growing musically, and watching them become competent and independent. That’s the goal for me. I also think about legacy. Hopefully I can establish things that continue beyond me, and in the same way I still talk about my old teacher—a Malaysian lady who ended up in Dominica—they can talk about me.’

Moving forward, Darren hopes to bring more Caribbean influences to DC’s youth, beginning with steel pan in the classroom. He can’t play, but can teach it, and says it’s a more exciting, rhythmic alternative to the tired recorder. He’s also eager to establish an all-inclusive children’s choir in the city.

‘This is the island life speaking, but everything is communal in Dominica. I don’t see that here, if the music program isn’t attached to a school. I’m trying to figure out my place in DC and what I can contribute.’

Back home, Darren’s sister became a lawyer. He thinks he made the right choice.

‘There’s a phrase, ‘People who make music cannot be enemies.’ Just for a moment, when you get lost in the music, all the ills of the world are gone.’