‘We’re Stewards of the Old Architecture of Georgetown’

Centuries before the name Marie Kondo sparked joy (and fear), people lived with very little stuff. Closets weren’t a commodity, and hardly any time was spent in the bathroom and kitchen—organizing, socializing, or otherwise.

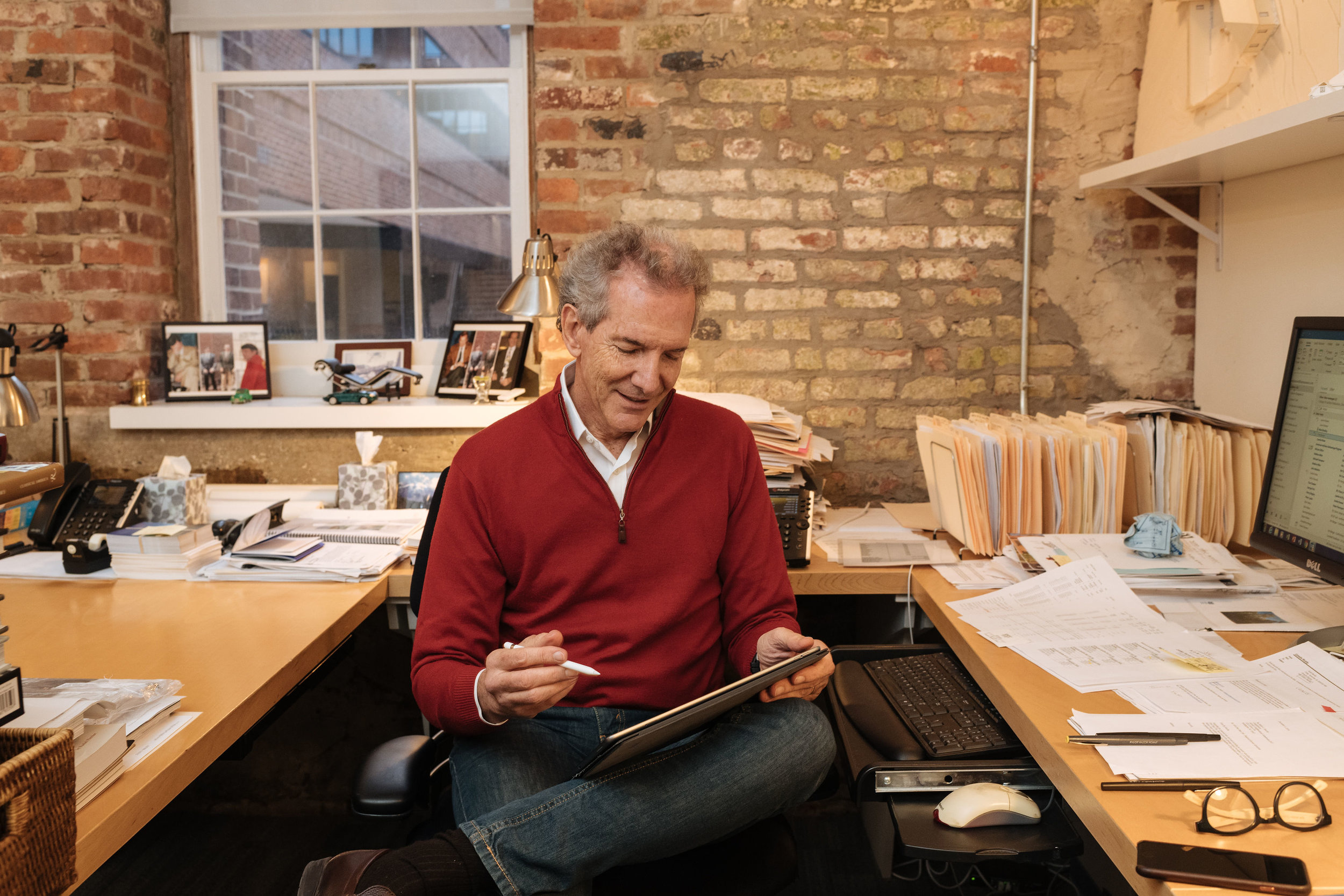

Now, architect Ankie Barnes’ job is to gently drag Georgetown’s historic residences into the modern age.

‘There’s a fine balance between preserving the scale of Georgetown and what’s best about it, and respecting the history, while adapting the houses again and again for use in modern life. It keeps us happily employed and gives the buildings a new lease on life. We’re stewards of the old architecture of Georgetown.’

Ankie became said steward in 1983, two years after escaping an apartheid future in his native South Africa. He was a qualified architect back home, but knew he’d struggle to find a job in the U.S. without an American degree, and decided to earn a Master’s in New England.

‘After graduation, I came to DC strategically. I found New England extremely cold, and there wasn’t much serious practice of architecture south of DC. Now there’s much more in Atlanta and Miami, but they really were not at the same level 35 years ago. DC was warmer, and more international—where my then-stronger accent wouldn’t stick out as much.’

Ankie worked for a Georgetown firm for seven years, where he met his business partner. Together, they broke out on their own in 1989 and founded Barnes Vanze Architects. Since then, the firm has moved four times—all within a three-block Georgetown radius.

‘The scale of the architectural fabric in Georgetown completely suits what we do. Clients are always struck by it and are better sponges of architectural discussion when they come to Georgetown. They park on the street, they walk between the buildings, they go past a coffee shop, see the canal and the river, and the scale of the old buildings. The history is evident. Those are all good components of architectural discussions, no matter where we work.’

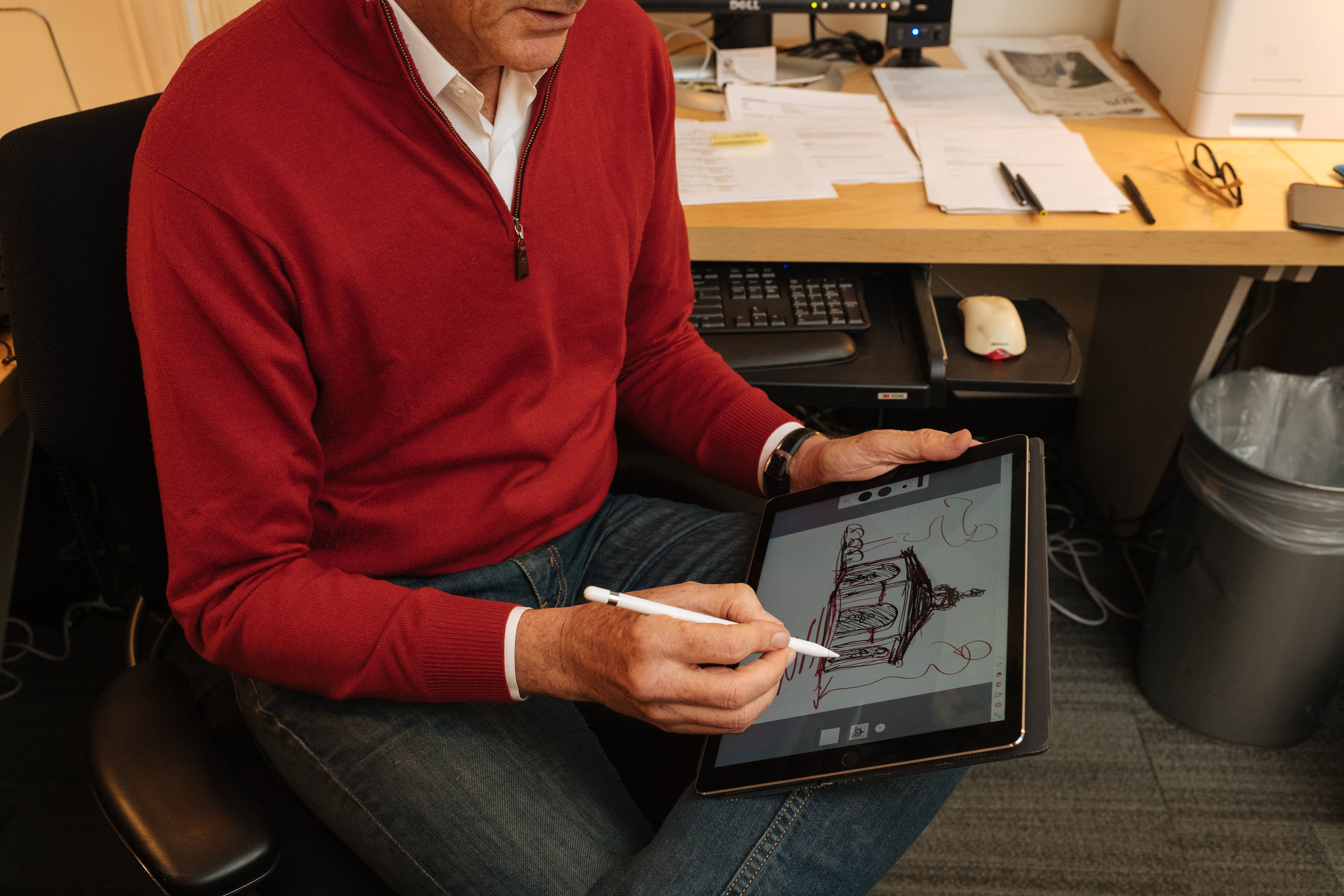

With more than 1,500 projects completed since the firm’s inception, Ankie says the key is listening to the client, and building a great version of what they want—not what he thinks is great. Ankie begins by involving every member of the household and identifying their individual strengths of expression—whether verbally, or three-dimensionally.

‘We ask them to write a short essay describing a day in their life in their favorite house. They each do it, and it makes people sit back and think about what they really want individually. Clients reveal things they didn’t know they wanted.’

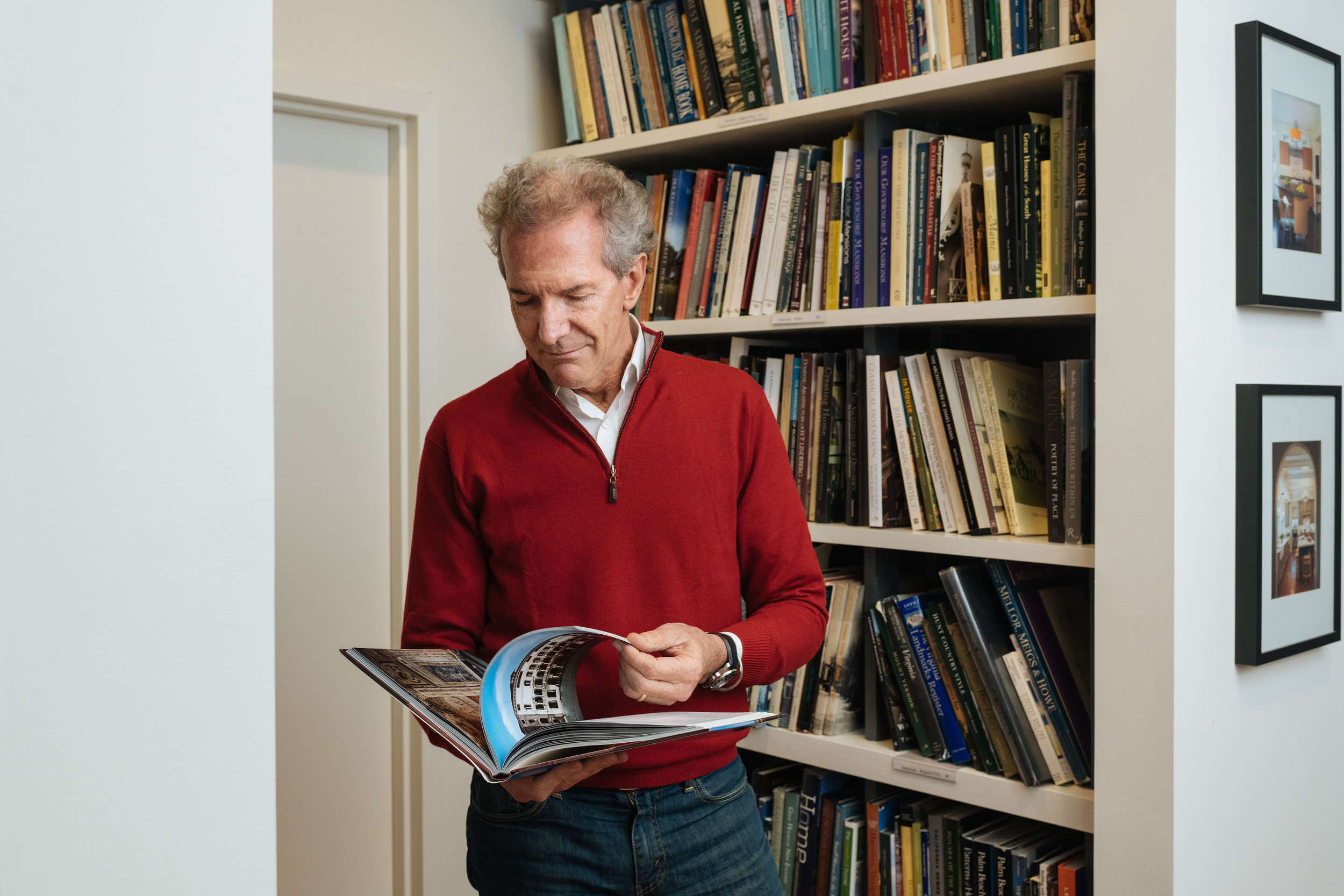

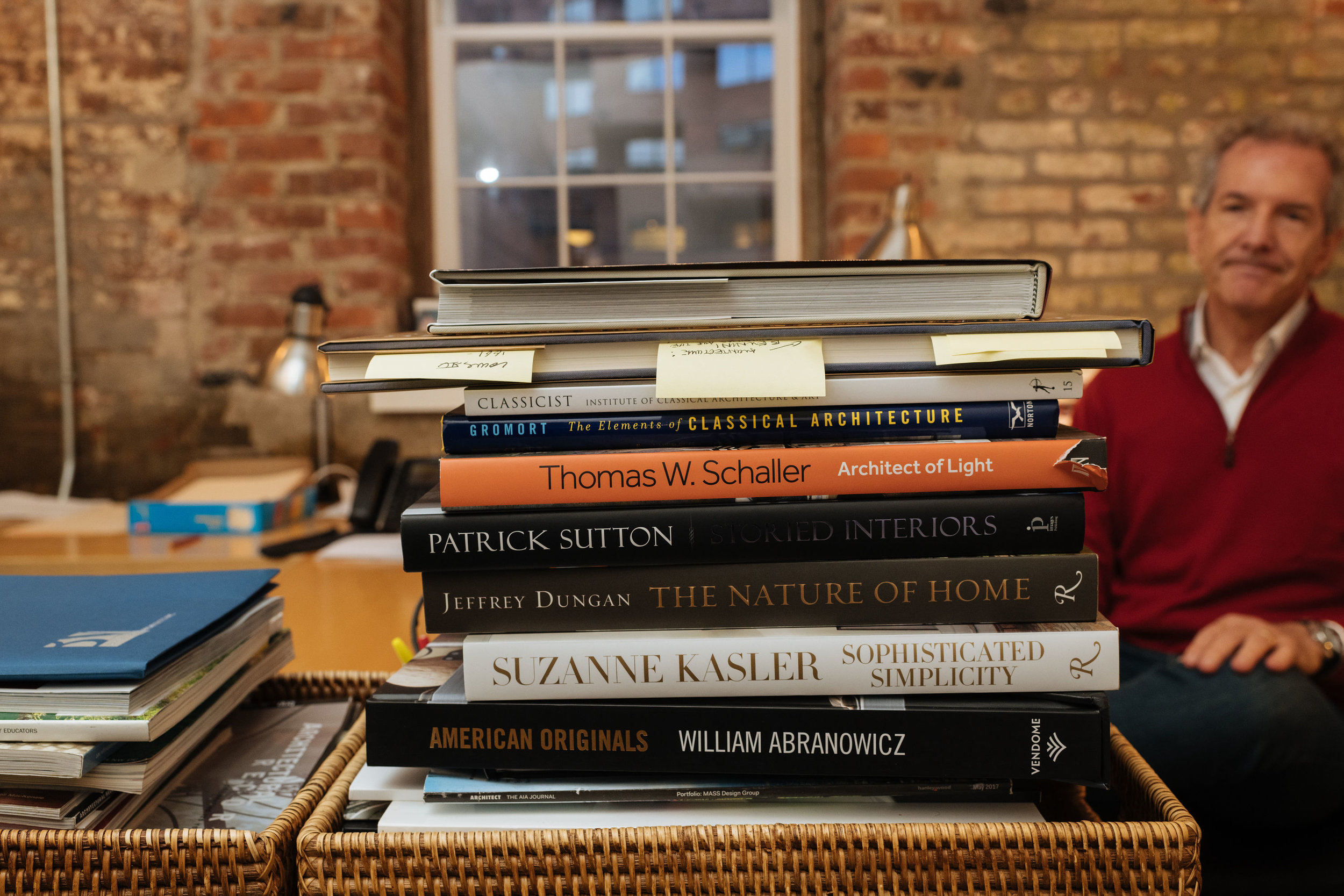

From there, clients select five to 30 images that capture the things they really like. Ankie mines those images for the visual clues needed to find ‘a touchstone sensibility or two’ to guide many of the aesthetic choices.

‘We’re always trying to make a new home for a family. If they’re happy at home, it’s good for the marriage, it’s good for the kids, it’s good for everybody. It’s very gratifying.’

Ankie’s favorite projects don’t necessarily equate to size or prominence, but rather the interest and passion of the client. One of his most memorable was an arts studio for a retired lawyer in his sixties who always dreamed of being a painter.

‘We built him a teeny studio that was a few hundred square feet in his suburban garden, and it was one of the greatest pleasures for me because it spoke to something that had been in his soul for 40 years, and he finally came to me and was so excited. He was very talented and we all got energized by the mission of the project.’

But architecture has always energized Ankie. By 14, he knew it was the path that best captured the intersection of art and science, as well as his interest in the environment. He took basic courses in everything from construction to woodworking, served as a draftsman for an architect—‘the lowest of the low apprentice’—and worked every vacation.

Like most architects of his time, Ankie was trained largely as a modern architect. Since his practice has matured, he says he’s become more respectful of the importance of a classical education.

‘Architecture isn’t a place for trends. It’s a place for ideas with lasting value. It’s a built art for 50, 60, 200 years. The best modern buildings have many underlying characteristics that they share with the classic. Things that everyone finds useful and beautiful. They can’t be too specifically built to one purpose, but rather flexible enough to work for the next generation.’

In other words, Georgetown. Ankie says the scale of M St and Wisconsin Avenue is world-class—a spectacular design that’s stood the test of over two centuries.

‘It’s some of the best in the whole nation because there’s a wonderful mix of residential scale buildings with apartments and rooming houses above them, and first floors designed for commercial. To this day, there’s something about the energy of the street and the casual interaction with others that is a really good example of a fairly dense urban fabric that’s very successful.’

Ankie’s firm has worked closely with many neighborhood businesses, renovating shop fronts and making them ‘their own best self,’ while still adhering to historic preservation guidelines. A Georgetown resident himself, Ankie feels lucky to have stumbled into a profession that not only suits him, but is reflected in every aspect of his life.

A profession that sparks joy.